“Progress in AI is something that will take a while to happen, but [that] doesn’t make it science fiction.” So Stuart Russell, the University of California computing professor, told the Guardian at the weekend. The scientist said researchers had been “spooked” by their own success in the field. Prof Russell, the co-author of the top artificial intelligence (AI) textbook, is giving this year’s BBC’s Reith lectures – which have just begun – and his doubts appear increasingly relevant.

With little debate about its downsides, AI is becoming embedded in society. Machines now recommend online videos to watch, perform surgery and send people to jail. The science of AI is a human enterprise that requires social limitations. The risks, however, are not being properly weighed. There are two emerging approaches to AI. The first is to view it in engineering terms, where algorithms are trained on specific tasks. The second presents deeper philosophical questions about the nature of human knowledge.

Prof Russell engages with both these perspectives. The former is very much pushed by Silicon Valley, where AI is deployed to get products quickly to market and problems dealt with later. This has led to AI “succeeding” even when the goals aren’t socially acceptable and they are pursued with little accountability. The pitfalls of this approach are highlighted by the role YouTube’s algorithm plays in radicalising people, given that there is no public understanding of how it works. Prof Russell argues, reasonably, for a system of checks where machines can pause and “ask” for human guidance, and for regulations to deal with systemic biases.

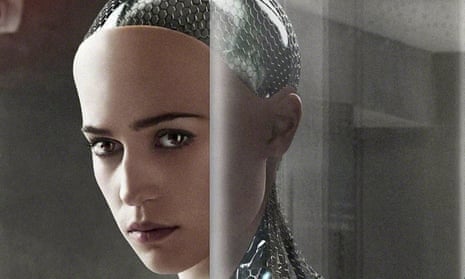

The academic also backs global adoption of EU legislation that would ban impersonation of humans by machines. Computers are getting closer to passing, in a superficial way, the Turing test – where machines attempt to trick people into believing they are communicating with other humans. Yet human knowledge is collective: to truly fool humans a computer would have to be able to grasp mutual understandings. OpenAI’s GPT-3, probably the best non-human writer ever, cannot comprehend what it spews. When Oxford scientists put it – and similar AIs – to the test this year, they found the machines produced false answers to questions that “mimic popular misconceptions and have the potential to deceive”. It so troubled one of OpenAI’s own researchers that no one knew how such language is being made that he left to set up an AI safety lab.

Some argue that AI can already produce new insights that humans have missed. But human intelligence is much more than an algorithm. Inspiration strikes when a brilliant thought arises that can’t be explained as a logical consequence of preceding steps. Einstein’s theory of general relativity cannot be derived from observations of that age – it was experimentally proven only decades later. Human beings can also learn a new task by being shown how to do it only a few times. Machines, so far, cannot. Currently, AI can be prompted – but not prompt itself – into action.

Ajeya Cotra, a tech analyst with the US-based Open Philanthropy Project, reckoned a computer that could match the human brain might arrive by 2052 (and come with a $1tn price tag). We need to find better ways to build it. Humans are stumbling into an era when the more powerful the AI system, the harder it is to explain its actions. How can we tell if a machine is acting on our behalf and not acting contrary to our interests? Such questions ought to give us all pause for thought.